The life of Indian costume designer Bhanu Athaiya is one of quiet power and many hidden talents.

- Fashion

Meet the First Indian to Win an Oscar

- ByNandini Bhalla

Bhanu Athaiya won the Academy Award for Best Costume Design for ‘Gandhi’ (1982)

Known as the doyenne of costume design in India Cinema, Bhanu Athaiya’s journey as an artist and designer is punctuated with many firsts. She was the first woman to join the prestigious Progressive Artists’ Group, the first Indian Indian to win an Oscar in 1983, and one of the first designers to showcase their collection at the first Calico Fashion Show in 1958.

The Word. speaks to Indrajit Chatterjee, Founder of Prinseps, the avant-garde auction house behind the exhibition ‘Bharat Through the Lens of Bhanu Athaiya’—curated by Brijeshwari Kumari Gohil—that explores and celebrates Bhanu’s contribution to the world of Indian cinema and the Progressive Art Movement.

The Word.: What is it that truly stood out for you when you first came sort of across Bhanu Athaiya’s Estate?

Indrajit Chatterjee: “When you look at Bhanu Athaiya’s Estate, the first thing that hits you is her accomplishments. But what is surprising is how little is known about her. She was of a certain personality, where she would never be in the front. And when you look at all that she has achieved, as compared to how little of her has been exposed in the news or art circles, that is what surprises one the most. But that also starts the journey of discovery about everything that Bhanu did, and that’s what makes this project very, very exciting.”

TW.: How did you get access to so many of Bhanu’s creations, photographs, and documents?

IC: “She had two connected garages in Breach Candy [in Mumbai]—which was also her workshop—that have trunks and trunks of material. There was some material outside the trunks as well, but, unfortunately, it did not survive. Even her connection to the Progressive Artists’ Group came to light at the very last minute, right before an Asia Society Exhibition on the Progressive Artists’ Group that was held in New York. While going through the catalogue, they realised that a female artist was part of the Group as well, and they photographed two of the artworks, one of which is on exhibit.

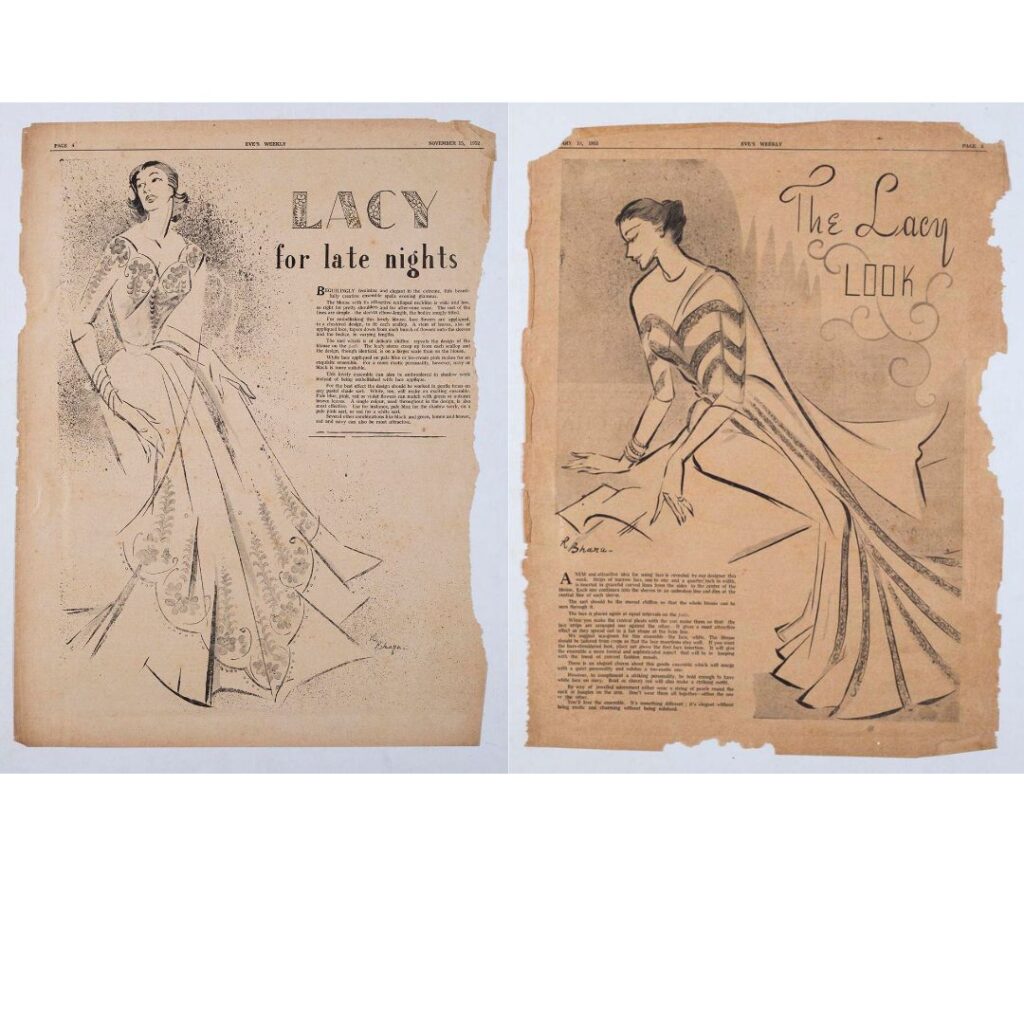

The other thing we wanted to focus on was fashion. She was one of the first fashion designers in India—in 1958, she had a fashion show, part of India ’58 Trade Fair, organised by Calico Mills and Ebrahim Alkazi. And again, that fashion aspect was not been documented at all, and it all came out of trunks…from the photographs that were meticulously archived by Bhanu herself. The costumes, seen in the second edition of ‘Bharat Through the Lens of Bhanu Athaiya’, are not recreated, they are the original costumes from that time, preserved by Bhanu. Also, many of the sketches we found have jewellery in them. Apart from these sketches, there are jewel pieces that were designed by her…and the reason I say ‘designed’ is because we found bags and bags of beads that she used to create them. She also applied 20 or 30 different innovations to costume design.

So we are trying to document it as much as we can, and it all happened because Bhanu was an archivist. She kept almost everything, she was an avid photographer—there are a tonne of photographs of what she did—and it all came out of the trunks in her warehouse.”

TW.: Tell us about Bhanu’s various facets you discovered while you were researching her life.

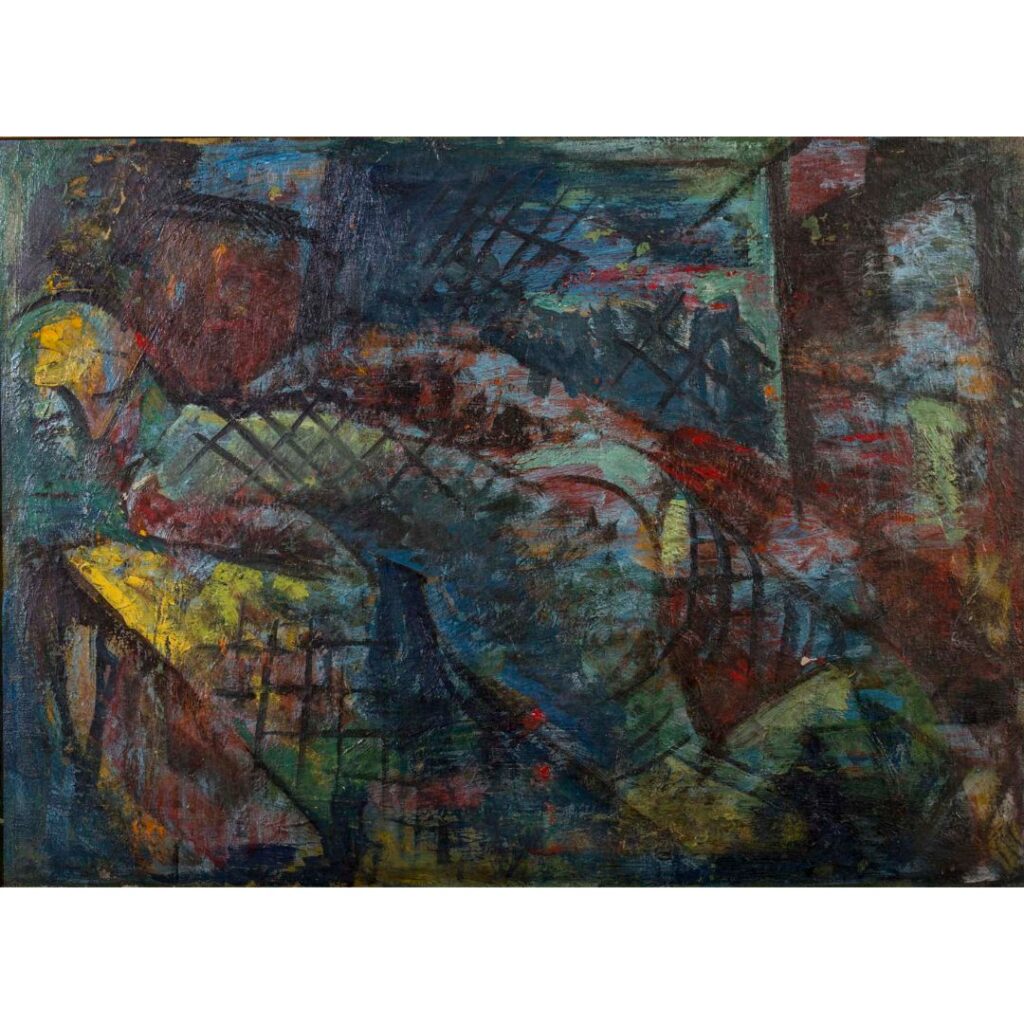

IC: “So the first one was art, and her contribution was huge. She was invited to join the Progressive Artists’ Group, which is considered to be one of the most important artists’ groups in India with other names like M.F. Husain, F.N Souza, S.H Raza… And they all knew each other, while she was invited to join that group because she won a gold medal at the JJ School of Art. So you can imagine the position that she was in. And with the variety of artwork she produced at that time, including the ‘Lady in Repose’ (1951), she was a very important contributor.

At Prinseps, we are proud to have been the ones to archive and document Bhanu’s artworks, and disseminate the collection amongst museums.”

Then we move on to the fashion part of attention to the fashion part. The 1958 fashion show, part of the Trade Fair, was not documented. Subsequently, in 1958 or 1959, again, it’s not very clear, but it’s there in a letter, there was another fashion show organised by Khatau [Mills], to celebrate the cloth produced in Indian Mills—fashion that utilised locally-produced mill cloth. She was also one of the board members of NIFT in 1996, so she also helped that organisation. She was an important figure in fashion and there’s almost no documentation around it.”

TW.: And does the research prove that Bhanu was way ahead of her times?

IC: “During the exhibition, which features ‘Lady In Repose’, a question was asked, ‘When Bhanu made an artwork like this, what were other artists doing at that time?’. The ‘Lady In Repose’ is an extremely abstract work with the form fading away. And an analogy was drawn that she was essentially a feminist at heart. No matter what she did, she never showed the female figure. The painting itself was so avant-garde, and the other painters at that time were making copies of Ajanta and Ellora or much simpler artworks, whereas this one was way ahead of her time.

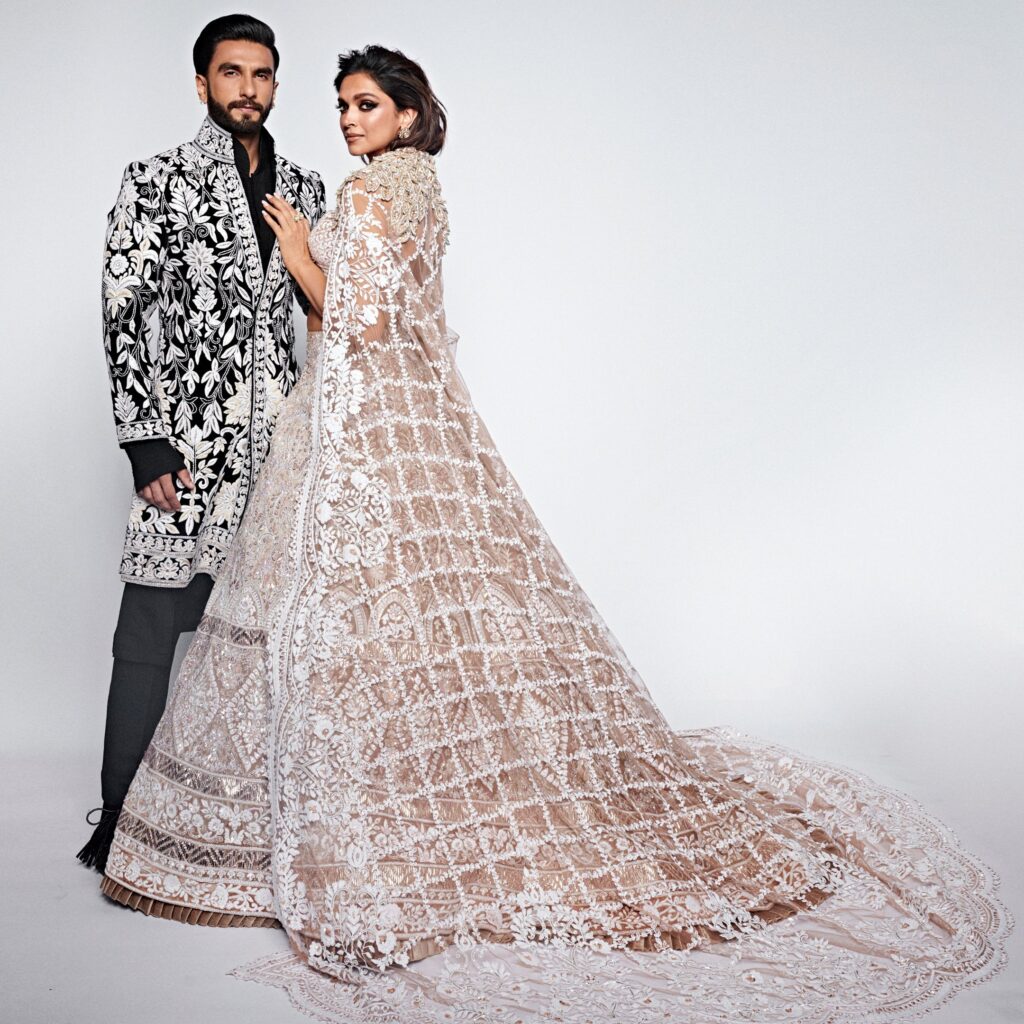

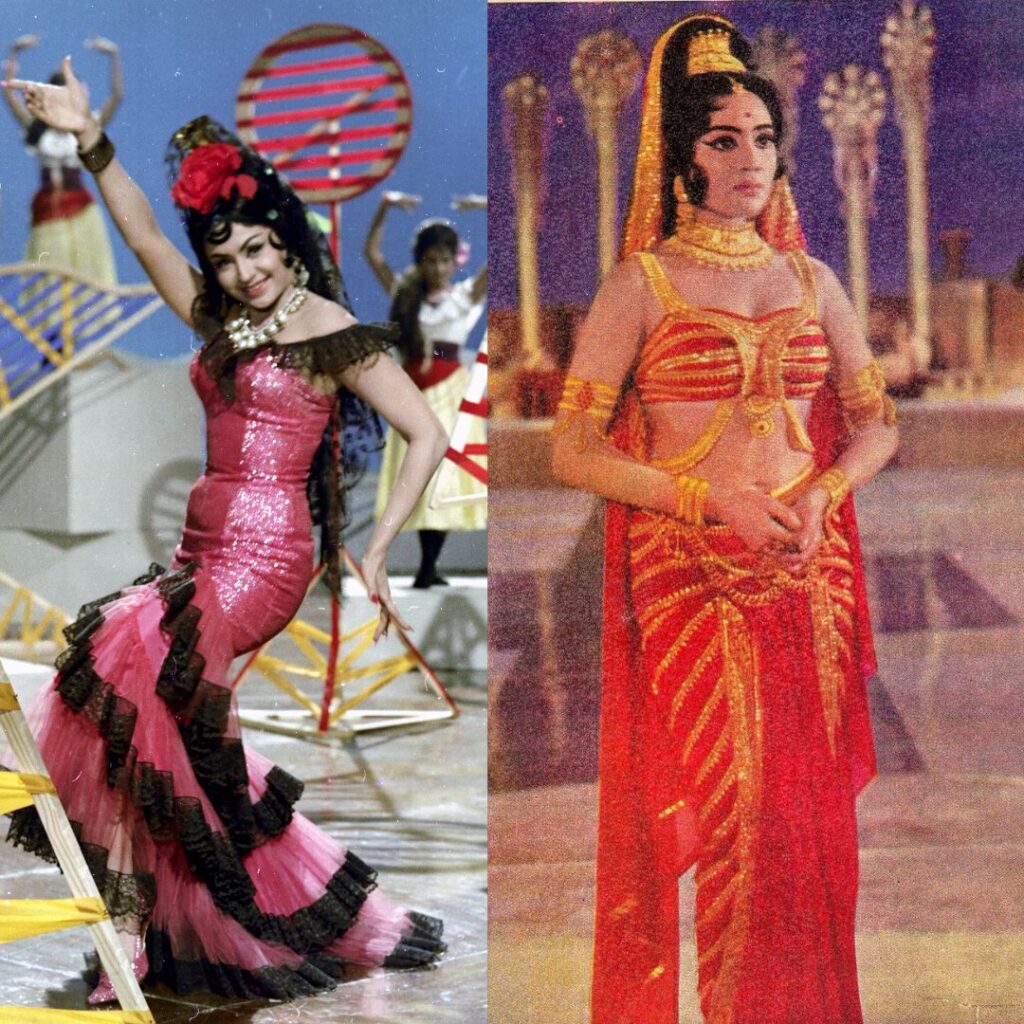

I’d like to think that she was so avant-garde because she was highly trained…because of her upbringing in Kohlapur, where she was surrounded by art and film. Bhanu’s father [Annasaheb Rajopadhye] was a self-taught artist. She also was one of the very few people who won the ASTEF scholarship from the French government to study in France—so she was very exposed to fashion overseas as well. So her upbringing, her education, and her overseas experiences opened her mind and that’s why what she produced was way ahead of her time in many aspects. I mean, look at all the costumes that she made, the innovations in the sari. One of the saris that you saw at the exhibition, I am not even sure if you’ll be able to read drape it once it’s taken off the mannequin. People speak about Mumtaz’s sari that Bhanu created, but that’s not sari at all—it was made to look like a sari with different layers. And this particular area, about the innovations she created, is still under research, and hopefully, in the next year and a half, we will be able to document many more of these innovations.”

TW.: Is there anything else you’d like to add from what you have learned about Bhanu?

IC: “One of the areas of discovery has been Bhanu’s costume design, and we are looking for an art critic to put it into perspective. A very unique quality about Bhanu as a costume designer was that she made detailed sketches of her costumes—most people would make what I would call conceptual sketches, like a simple line sketch with some bullet points, but she made extremely elaborate costume sketches. Some of the sketches are so detailed and elaborate that they are even better than miniature paintings. And she could do that because she was an artist at heart. With over 500-odd elaborate sketches, her costume design is an artistic form.”

TW. Tell us about the recreation of Bhanu Athaiya’s fashion show that you are working on.

IC: “We are going to recreate the 1958 fashion show, wherein we found photographs of where it was held—at Pragati Maidan in New Delhi. We have the costume sketches, photographs of the models, of the crowds…and we will take all of this information to create an AI-induced digital version of the entire fashion show… And people would be able to attend the screening of the 20-minute clip as though they are a part of the audience.”