- Culture & Travel

Why Do Sexy Women Always Die in Horror Films?

- ByRadhika Bhalla

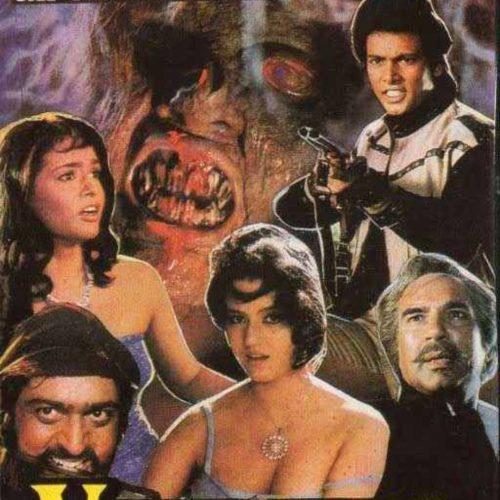

The poster for Aakhri Cheekh, 1991.

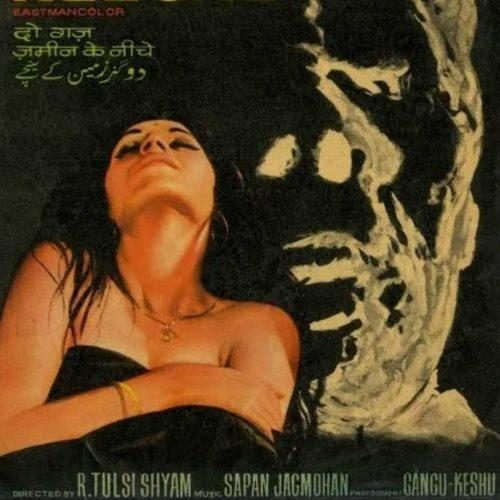

It’s a plot we’ve seen before: the sultry actress in the horror film invariably gets attacked, possessed, or killed. Almost punished for her sexiness, her death is implicit the second she makes an appearance on screen. And later, when it’s time for her to die, she takes longer to fall to her death than her male counterparts do…

What is it about sexy women and the horror/thriller genre? Studies reveal that in such films, the woman who displays overt sexiness, a desire for pleasure, or a drive for sex, nearly always dies. And yet, the genre thrives on her sexiness. It’s a Catch 22 situation.

More often than not, horror combines lust with bloodlust…a “masochistic fantasy” of sorts when it comes to the female protagonist. And a number of cinematic tools are used to do this—’The Chase’ scene, for instance, will show her running away from the murderer, and as the chase progresses, articles of her clothing progressively come off. In addition, the camerawork is most often lecherous, panning across her body as she looks terrified, fleeing for her life.

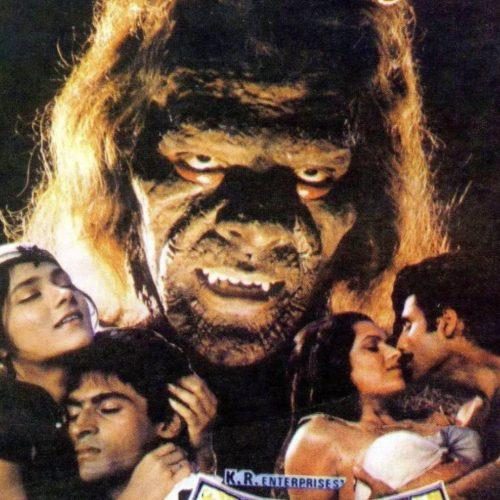

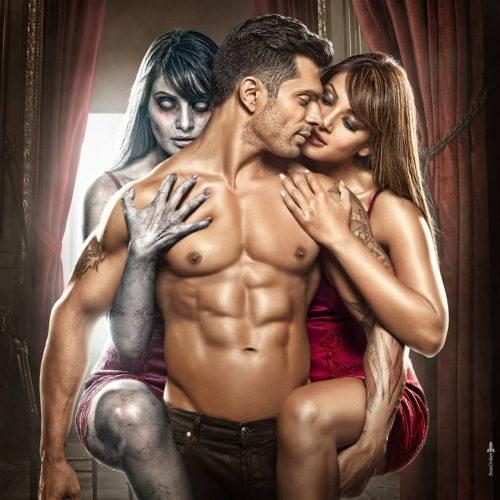

The examples are plenty—it began with the shower scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho [1960], followed by the Ramsay Brothers films from the 1980s and ’90s, Sarah Michelle Gellar in I Know What You Did Last Summer [1997], Courteney Cox in Scream 2 [1997], Angela Vint in Urban Legend [1998], Aakhri Cheekh [1991], Bipasha Basu in Alone [2015], The Final Girls [2015], and many more.

A study reveals that in slasher films, the gender dichotomy is more pronounced, and sexual women are specifically attacked. They also take longer to die than men, and are shown being terrified for more seconds on-screen than men are. Then, there is the “final girl” trope—the last surviving young girl, or group of girls, who finally confronts and kills the murderer. A term coined by American professor Carol J. Clover in 1992, this character gains the power in the end to overcome the killer. But before that, she is subjected to “abject terror”, a sensation that can best be showcased on a woman for a primarily male audience.

The sadistic voyeurism comes with a moral undertone too—that the ‘promiscuous’ or fun-loving young girl gets ‘corrected’ or ‘purged’ of her desires for personal pleasure through this process. At a subliminal level, that is a dangerous message to send out to the audience at large.

Feminists have long argued that hyper-sexualised portrayals of women in horror films are de-humanising, and that the male gaze reduces women to mere objects to be possessed, attacked, and discarded. In fact, many state that the genre often showcases the extremes of patriarchy, focused on controlling a woman’s liberty, sexuality, and power.

As a result, such movies end up conveying and reinforcing uncomfortable notions. The horror and thriller genres may be intended for kicks, but it’s the underlying message that is truly scary.

READ MORE

- Gauri Khan, On Her New Experience Centre In Delhi, Her Favourite Spot At Home, and Great Décor Advice

- With IRTH’s New Store in Noida, The Brands Adds To Its Joyful Delights

- Ranbir Kapoor’s New Perfume, ARKS Day, Reminds Him of His Childhood

- Your Interiors Will Love The Colour and Design Predictions By Asian Paints’ ColourNext Forecast for 2025

- “India is an Incredible Source of Inspiration for Me, and I Want to Connect With the Hearts of Indian Women”