- Culture & Travel

Celebrating the Trans Community: The Aravani Art Project

- ByRadhika Bhalla

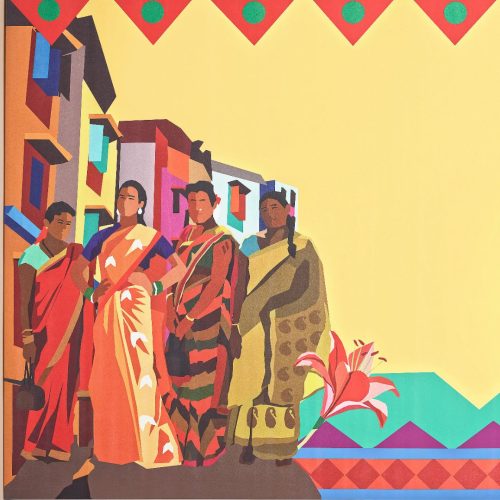

Members of the Aravani Art Project pose for the Walkers & Co. campaign.

Whose face deserves to be on grand billboards across the country? While the beautiful and the powerful have long held this prerogative, a wonderful new campaign is celebrating the true heroes of the trans community. This month, Walkers & Co. has created a powerful platform to recognise the tireless and impactful work that the Aravani Art Project has been doing over the years, uplifting and supporting members of the trans community through public art.

While you’re out on the streets, remember to look up and spot these billboards in Delhi NCR, Mumbai, Goa, Pune, Kolkata, and even at the airports across the country. On them, you’ll spot an illustration of the trans women from the Aravani Art Project in saris, framed by the inspiring motto from the Keep Walking ethos—”The Ones Who Keep Walking, Move The World Forward”.

In an exclusive conversation, The Word. caught up with Poornima Sukumar, the founder of Aravani Art Project, to discuss this important collaboration, the work the community undertakes, and the impact they have had on the trans community.

The Word.: Tell us about the collaboration between Aravani Art Project’s and Walkers & Co.

Poornima Sukumar: “Especially now, it is so essential for us to get the kind of visibility that Walkers & Co. is providing us with. While our project already is quite known, we are lagging behind with our social media outreach, because there is so much we’re doing on-ground. So Walkers & Co. is helping us do that, and we have been given so much freedom of thought and expression in creating a special work for them. It has worked out really, really well.”

TW: Both Walkers & Co. and the Aravani Art Project are powerful platforms—what creative exchanges took place in this project?

PS: “Walkers & Co.’s tagline, ‘Keep Walking’, has always held deep meaning for us. Even before they approached us, we would use this phrase as a collective, because that is what we do all the time, we just keep moving forward. There are several challenges trans people face…this could be on a personal level, like a member coping with their mental health, or as a collective of not getting the right project.

Working on this collaboration has been truly meaningful, because ‘community’ is important to both the Aravani Art Project and to Walkers & Co.. The synchronisation—in terms of our priorities, the community, people and their feelings, and their celebrations—was beautiful. Of course, art is a big part of our similarities too, and it matters that we create the space for that art.

for the Walkers & Co. collaboration.

TW: What does the term Aravani mean?

PS: “So the assumption is that Hijra means transgender, which is wrong. Hijra is also a culture, it’s a cult, and Aravani is one such cult. Many years ago, I happened to attend one of their festivals, in 2010, called Chitra Pournami that takes place in Tamil Nadu around April/May every year.

There exists a temple there, dedicated to Aravan, the son of Arjun from the Mahabharata. In the epic, Aravan decides to sacrifice himself for the victory of the Pandavas, but before that, he requests to be married before he dies. So, lord Krishna takes the form of Mohini (a woman), to fulfil his last wish. This entire saga is performed in that temple every year, with a congregation of 25,000 to 30,000 trans women who come and get married to Aravan, and the very next day, they all get widowed.

Attending this ceremony felt like being in a parallel universe…the day they become widows, I don’t know what happens, but they take out years and years of frustration. It’s very powerful, moving, and disturbing, at once. That was my first-ever exposure to the community; I had never spoken to a trans person before. Yet, even once I left, the term ‘Aravani’ kept following me [which means a person who is married to Aravan]. The word just moved me so much, I decided that if I ever do anything impactful, the word Aravani would be used somewhere.”

TW: When did you form the Aravani Art Project?

PS: “The project came together over several conversations with my transgender friends. I particularly wanted to work with people who are both economically backward and didn’t have the opportunity to complete their education…who might be considered the bottom rung of their community. I thought art would be a great way to allow members of the trans community to get some time away from their problems… We were very sure we didn’t want to do an art class within four walls; we wanted it to be out there, because these members needed to be seen, to create a bridge with the world, for people to have conversations with them directly. Rather than visiting people in an NGO, and I am not disregarding their work, I felt that we needed a fresher approach. And that is how we chose the streets as the canvas.”

TW: What has been the response of onlookers while the art is being created?

PS: “Every time we go to our site, the first reaction we always get is of laughter, teasing, and disbelief over how we will manage to create artworks of such scale. When we, sometimes, struggle to climb the scaffolding, people pass comments like, ‘See, that is why these women are not supposed to do such things’. But we really don’t care about it; we just go and do our work, which is why it creates a bigger impact.

We have had some really terrible experiences, especially from men. But the women are always amazed, they’ll tell us how incredible it is what we are doing, and how proud they feel. We have never had a bad comment from women. And children are always willing to come and paint with us, because kids are so non-judgmental…it’s so interesting that they are without those inhibitions. The men, however, are dismissive and curious to see how far we will go, and while we are climbing, they will laugh at our backs.”

TW: Does their perception change over time?

PS: “Absolutely! After around four rigorous day on site, these very men change their minds about us… They’ll treat us to tea or biryani, and people literally shower us with snacks, or juice every other hour! We end up collecting so much to eat, it’s a lot of fun. The generosity and acceptance of these strangers is so important, because the trans women have never received it. And the act of creating these artworks is so empowering for them, because nobody is preaching to them…they are taking the initiative of doing things on their own. I feel that impact lasts much longer.”

TW: How do you get permission to paint on the streets?

PS: “When we started out, we were entirely self-funded. I used to earn enough as an artist to share a bit for Aravani, though I was always living on the edge…I’d make around ₹20,000 and around half of that would go towards doing something for the trans women. I must say, it was much easier for us, around seven years ago, to paint on a wall. It has become much more difficult now because everybody is involved and people are a lot more opinionated and aggressive; it is a kind of politics. Now, for anything we do, we have to run it through so many permissions. As a result, we now largely do commissioned projects and are grateful that we are paid for them.”

TW: And you also collaborate with government institutions…

PS: “We did a project with the Election Commission last year. People are really open to our work, but it needs to come from a higher authority to materialise. I think what is working for us is the fact that we employ the local trans women of a region to add a local flavour to the artworks. As a result, even the government has reason to support us.

We have teams in Bengaluru, Chennai, Mumbai, and Delhi, and we work with the community of the region we go to. For instance, we painted the district children’s court in Warangal, Telangana, which was unheard of. They wanted the court to be much more approachable for kids, so we invited the local trans women from Warangal to paint with us and gave them the exposure. We did something similar in Jaipur, and the leader of the trans community there was so impressed, she started undertaking government projects with her people.

Aravani Art Project has become a form of shelter for these people. The trans community has to prove themselves throughout their lives, there are risks everyday in their lives, be it while travelling in a bus or when they choose to go for sex work. But if they are caught or when they feel like they are in danger, they talk about the work they do, they show their ID card. And people start looking at them with different eyes, even the cops are appreciative. In fact, we are hoping to paint some police stations next year, especially in Bengaluru.”

TW: Some of the portraits that are painted don’t have any features on the face. Is there a reason behind that?

PS: “Yes, that is because when we create very detailed faces, some people have a problem with the identity of how it looks. Especially corporations don’t want the portraits to look like anybody in particular. So we keep altering the style depending on the requirement.

We are quite flexible with the themes, as well, because we realise that apart from creating works around gender, equality, inclusion, and diversity, we also need to talk about other causes. So now, we are also creating works on the environment, and we are working with other cis-women, other communities, and migrants. Aravani is not stuck to just their own struggles, but also honours how everybody else is fighting their fights.”

TW: Do share some success stories of the artists…

PS: “There are so many! Each member has had some positive shift in the way people now look at them, which includes members of their family and neighbours. And this is a very big affirmation for them because that’s where the discrimination starts. Now, they are recognised as much for their art, and with so many articles about them in the papers and campaigns, people recognise them when they step out too, which is incredible! People will actually stop them on the streets to ask, ‘Aren’t you guys from Aravani?’. Nobody talks to me, which is great because I am not the face of Aravani and I never want to be. If anybody asks me any question, I always redirect it to them because only they can answer them.

One of the trans women met with an accident, where she lost her leg. But she is back to work now, wearing prosthetics. And another person, Karnika, who is also part of the Walkers & Co. campaign—started out as a young boy named Pradeep, who was figuring out their sexuality. She was very coy, not confident, and did not understand that they were going through gender dysphoria.

So many of these young children run away from their homes because of the pressures from their families, but when they join the hijra community, it’s nothing less. They are vulnerable and are still treated badly—they have to enter sex work if they are pretty or begging if they aren’t, and give 50 percent of whatever they earn to the person who is taking care of them. There are several such rules within the trans community and when you try and escape from one, you’re caught in another.

Aravani has given these members a safe space and the leverage to leave such oppressive situations; most of the people in our collective are not part of the hijra system, because they don’t like it, they don’t believe in it. Here, they have something to bank on, emotionally and financially.”

READ MORE

- Gauri Khan, On Her New Experience Centre In Delhi, Her Favourite Spot At Home, and Great Décor Advice

- With IRTH’s New Store in Noida, The Brands Adds To Its Joyful Delights

- Ranbir Kapoor’s New Perfume, ARKS Day, Reminds Him of His Childhood

- Your Interiors Will Love The Colour and Design Predictions By Asian Paints’ ColourNext Forecast for 2025

- “India is an Incredible Source of Inspiration for Me, and I Want to Connect With the Hearts of Indian Women”