India’s ambitious wildlife relocation endeavour saw considerable fanfare, but as the death toll hits nine, we discuss how Project Cheetah has fared.

- Culture & Travel

The Cheetah is Dead…Again

- ByDiya J Verma

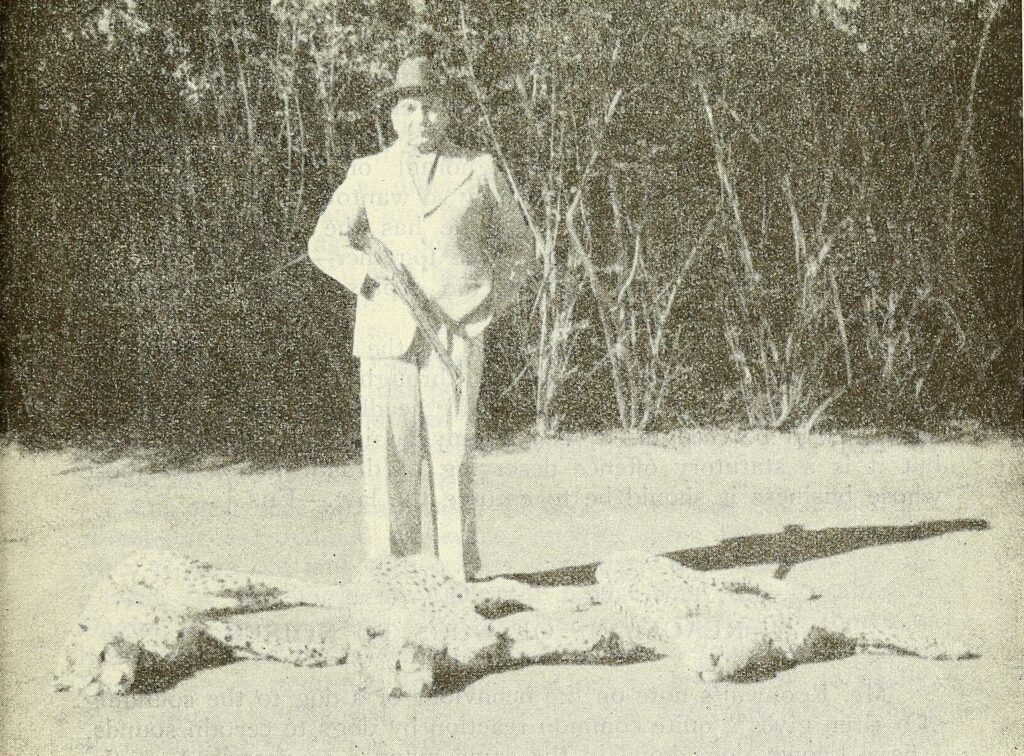

Archival photograph of the Prince of Wales and the Maharaja of Gwalior with a tiger and two leopards

[Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons]

Ten months, nine deaths—has Project Cheetah underscored the repercussions of wildlife rehabilitation? Perhaps. The international scheme involved translocating 20 Southeast African big cats to Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park, with hopes of establishing a self-sustaining population of cheetahs within the country. However, in a span of a year, six adult cats and three cubs have succumbed to injuries, infections, and a presumed hostile environment.

The cheetahs went extinct soon after India gained independence from British rule. In 1948, Maharajah Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo of Surguja State shot the last three surviving Asiatic cheetahs, deeming them extinct. The Kuno National Park cheetahs Sasha, Daksha, Uday, Suraj, Tejas, and Dhatri sadly met the same fate—but this time around, the circumstances were different. Most of the felines that died were held captive in specially designed enclosures called bomas, with just a few roaming about in the wild. While Sasha and Uday died of a renal infection and cardiovascular ailment, respectively; Tejas and Daksha succumbed to fatal injuries ensuing a physical confrontation with their counterparts. Surya’s untimely death was blamed on the maggot-infested radio collar fitted onto the cheetahs’ necks, which seemed to have obstructed movement, while the litter of cubs were overwhelmed by heat and malnourishment. Dhatri’s demise is under investigation.

These deaths pose pertinent questions: Are endangered species at an increased risk of extinction due to translocation? Is it ethically and ecologically feasible?

An archival photograph of Maharaja Ramanuj Singh Deo with the three cheetahs he killed in 1948, which led to the extinction of the species in the Indian subcontinent. [Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons]

Zoologists argue that the rehabilitation programme was avoidably rushed, many hold the dearth of space and prey culprit. Yet, others believe that the prolonged quarantine conditions the cats were subjected to ahead of their arrival could’ve potentially impacted their psychological and physical adaptive capabilities, “weakening” their immune system. Then there are those who contend that the South African felines weren’t acclimatised to the high humidity levels in India, resulting in their collar-borne maggot infections and inevitable demise.

Others claim that the consecutive deaths in a short span are far from unusual—owing to the high stress of relocation—and will plateau over time. The Environment Ministry also put forth that cheetah cubs have a significantly higher mortality rate relative to tigers and lions, and a mere 10 percent make it to adulthood. Meanwhile, Rajesh Gopal, the head of the cheetah monitoring committee set up by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), commented on the radio collars. “We have been using collars in wildlife conservation for around 25 years. I have never come across such an incident.”

But these deaths pose pertinent questions: Is it ethically and ecologically feasible? Are we achieving the greater good—or not? Are endangered species at an increased risk of extinction due to translocation? These concerns are the real elephant in the room that must be addressed.

In conversation with a leading publication, Professor Sarah Durant of the Zoological Society of London concludes, “Any country that re-introduces a large carnivore deserves to be applauded. However, there does seem to be an excessive number of losses at Kuno; there needs to be a rethink of how they’re managing the Cheetah Project and halt future re-introductions for the moment.”

READ MORE

- Don’t Be Late to Meet Katrina Kaif…

- This Homegrown Beauty Brand Cares About Science and Your Skin

- From Exquisite Tea To Handcrafted Textile And Plantation Furniture: Makaibari’s New Experiential Bungalow Is A Serene Retreat

- Tara Sutaria Hoards Candles, Listens to ’50s Music, and Cries When She’s Happy

- Zurich FIVE in Switzerland is the Celebrity Resort You Need to Visit